Submarine is a journey through the life of a witty, filthy, and

outrageously precocious fourteen-year-old boy. Oliver Tate’s

ambitions are to lose his virginity before it becomes legal, to discover

the cause of his Dad’s depression, and to find out why his mother is

‘getting surfing lessons—and probably more—from a hippy-looking

twonk.’ Trespass talks to Joe Dunthorne about the genesis of his

debut novel, the influence of his work as a poet on the piece, and the

challenges faced in reimagining the teenage ‘misfit’ hero.

You remarked previously that you didn’t plan Submarine as

much as have several good stabs at it, finding your voice as

you went along. It struck me that this decision not to plan is

very much in keeping with Oliver’s character, the desire to

jump into an escapade and see where it takes him.

That’s Oliver, he’s shambolic. Writing from his point of view you can

pretty much get away with anything, as long as it’s in keeping with

his personality…

Oliver is an idiosyncratic and contradictory protagonist. Was

his character fully fleshed-out in your mind before you set

pen to paper, or did he take form as the novel progressed?

Oliver pretty much came to the page fully formed. At the beginning

he may have been a little more fantastical—delusional maybe, not

just eccentric. You can see that side of his character at the beginning

of the book where he sees everyone around him as having weird

attributes or special powers. [Oliver is convinced that his neighbour,

a physiotherapist, is a ‘pansexual’ (a person who is sexually attracted

to anything) while the painter-decorator, in his paint-splattered

overalls, is obviously a ‘knacker’ (horse killer)]. I expected his

character to develop through the process of writing the novel. He

became more real.

It’s been sixty years since J. D. Salinger turned the misfit

adolescent into a fictional trope. Since Holden Caulfield, we

have encountered a motley pack of sexually anxious teens at

odds with their parents. Given that you’re covering such welltrodden

ground, how did you give Submarine its freshness

and edge?

Generally I don’t find referring back to similar works very helpful.

I’ve read Catcher in the Rye and Adrian Mole, but I didn’t go back

and read them again before I tackled Submarine. In fact, there were

works that people recommended to me as similar that I purposefully

didn’t read, like A Curious Incident [The Curious Incident of the Dog

in the Night Time, by Mark Haddon]. I just went ahead, hoping that

the novel would break new ground.

In a review in The Independent, Jonathan Gibbs expresses

jealousy that this generation of teenagers have Submarine,

while his generation had to settle for Adrian Mole, “written by

a woman as old as my mum, and no doubt as much with my

mother in mind as me.” (‘Submarine, By Joe Dunthorne’

02/03/2008). I noticed a cheeky nod to Sue Townsend in the

book: Jordana nicknames Oliver “Adrian” after reading his

diary entry “All the people I’ve ever kissed.” She’s clearly

poking fun here... Photograph by Eamonn McCabe

(laughing) Well, Adrian Mole was very uncool, and Oliver is cool. He’s not a geek, although he’s

sometimes unbearably pretentious.

Much of the humour, and many of the more poignant moments in the novel, seem to

derive from the gap between the narrator’s world and what we know, or suspect, is

actually going on. One of my favourite ‘love’ scenes is when Oliver’s girlfriend, the

down-to-earth Jordana, is hanging from the climbing frame and drools into Oliver’s

mouth. Oliver muses, “Jordana’s face is turning red…—sexual nervousness can do

that.” “I feel post-coital”. His self-delusion is frustrating, but also at times endearing.

He’s a totally unreliable narrator. A lot of the time I have him say “this means that” when the

reader is going no, it clearly means something else. I’m dropping clues throughout the book. So

you’re constantly thinking “what’s going on?” It was a lot of fun, toeing that line.

I imagine Submarine is a frightening read for parents. Your depiction of the mother and

father through Oliver’s eyes exposes the layers of miscommunication that can so easily

accumulate in a family.

I hope it has a scaring effect. One of my intentions is to make parents un-comfy. Everyone reads

partly for their own character, and my agent identifies with the mother. The idea of the level of

awareness that a fifteen year-old might have really makes her squirm.

Am I right in saying that Submarine is aimed at adults, as much as the teenage market?

I try not to think about readership too much when I write. I began Submarine on my Creative

Writing Masters at UEA, so I was writing it for myself and my group of friends. At the time I was

twenty-two. It’s broadly aimed at fourteen-year-olds up, I’d say. But Oliver is such an anomaly

anyway; it’s unlikely that someone picking up the book will be very much like him.

Submarine is about first times. First experience of a relationship, of sex, of death…everyone

can relate to these experiences. I’m not normally drawn to heavy material, I’m very wary of

being heavy-handed. Oliver’s character allowed me to approach these more serious themes,

because he takes it all so flippantly. He’s not prone to thoughtful moments, so the challenge was

to find opportunities for thoughtfulness.

The sadness in the novel is even more effecting, I found, because you’ve embedded

these moments in otherwise unassuming, even farcical scenes. I was struck by the chapter where Oliver takes his father to the fair, and puts him on “Shocker, The

Authentic Electric Chair Replica”, hoping that the ride will act as a placebo cure. It’s funny, but also a devastating scene in many ways. For me,

this was a predominant experience in reading the novel, this tension between

two very different emotions.

Oliver himself seems to inspire strong feelings and extremely polar reactions. I’ve had the full spectrum of responses to his character. Some people say he’s

cold, cruel, unfeeling, irritating, stupid…Other people think he’s a complete

hero, they love him, they think he’s funny,charming. It’s impossible to predict how

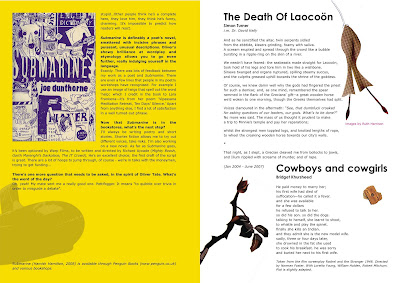

readers will react. Submarine is definably a poet’s novel,

smattered with incisive phrases and puissant, unusual descriptions. Oliver’s

showy brilliance at wordplay and etymology allows you to go even

further, really indulging yourself in the language.

Exactly. There was lots of feedback between my work as a poet and Submarine. There

are even a few lines that people in my poetry workshops have recognised. For example I use an image of twigs that spell out the word ‘help’, which I credit in the book to Lara Frankena—it’s from her poem ‘Vipassana Meditation Retreat, Ten Days’ Silence.’ Apart from anything else, I find a lot of satisfaction

in a well turned-out phrase.

Now that Submarine is in the bookstores, what’s the next step?

I’ll always be writing poetry and short stories. Shorter fiction allows me to try out

different voices, take risks. I’m also working on a new novel. As far as Submarine goes, it’s been optioned by Warp Films, to be written and directed by Richard Ayoade (Mighty Boosh,Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, The IT Crowd). He’s an excellent choice; the first draft of the script is great. There are a lot of hoops to jump through, of course - we’re in talks with the moneymen, trying to get funding...

There’s one more question that needs to be asked, in the spirit of Oliver Tate. What’s the word of the day?

Oh, yeah! My mate sent me a really good one. Pettifogger. It means “to quibble over trivia in order to misguide a debate”.

No comments:

Post a Comment